The push to decarbonize buildings falls into the category of tactics toward the outcome of electrification. Since 39% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are generated from the built environment, decarbonizing buildings by reducing their reliance on fossil fuels for heating and cooling is a strategy incentivized by local, state, and federal policy. How exactly do we create an all-electric building stock? All electric buildings are easier to develop from the ground up, but new construction traditionally represents 5% of the building stock at a given time. In this blog, we will explore how two existing building projects moved closer to all-electric.

Existing Buildings Are More Sustainable

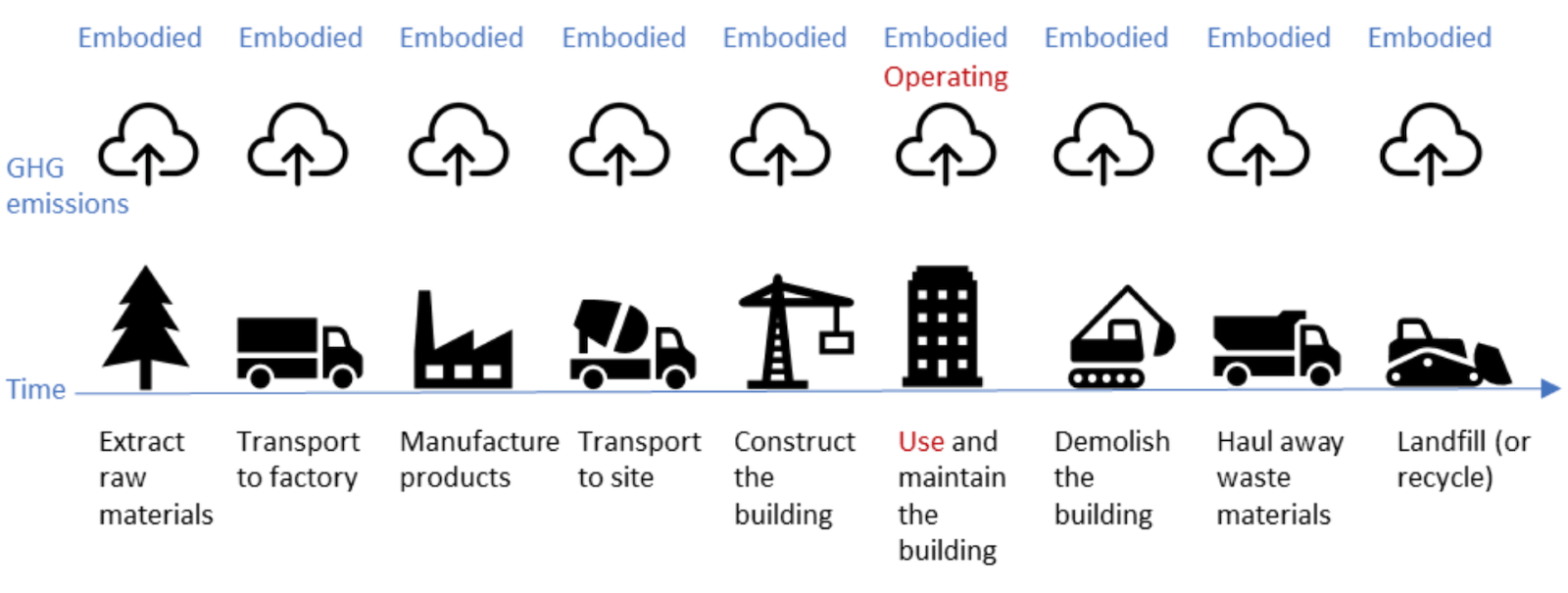

The materials required to build a new building account for 11% of the greenhouse gas emissions from the built environment. For that reason alone, reusing existing building stock in lieu of building new is a generally accepted concept. Even Fast Company got on the bandwagon last year with an article about adaptive reuse as a meaningful way of addressing the impact of increasing GHG emissions. Adaptive reuse is the process of reusing an existing building for a purpose other than it was originally intended. In Emerald’s portfolio, we have several examples of adaptive reuse of either retail to housing or manufacturing to housing/office – soon coming is a school-to-office. Sustainable Community Associates is in the process of renewing life at Nathaniel Hawthorne Elementary School, which will convert interior spaces to apartments while maintaining the exterior and common areas.

The National Park Service maintains the National Registry of Historic Places, a database of the Nation's historic places worthy of preservation. Authorized by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the National Park Service's National Register of Historic Places is part of a national program to coordinate and support public and private efforts to identify, evaluate, and protect America's historic and archeological resources. In some circles, there is disbelief that a historic building can be retrofitted and made sustainable – some historic requirements make it difficult to change wall assemblies or improve glazing performance. Walls and windows are the easiest way to improve a building's performance. Advances in construction materials, techniques, and systems have made it easier to create energy efficiencies in historic buildings. Glazing systems, envelope treatments, and even advanced HVAC systems such as VRF (variable refrigerant flow) are tools project teams use to achieve efficiencies.

Reducing Scope 1 Emissions Through Electrification

A building’s GHG emissions profile includes both Scope 1 (emissions created on site) and Scope 2 (emissions from purchased energy).

A building that converts from fossil fuels as a source for heating to all-electric heating sources naturally reduces its Scope 1 emissions. For example, in climate zones 5 and above, heating with a 97% efficient boiler may cost less than an all-electric system, but if measuring carbon impact, the site-energy source (grid emissions profile) is important to consider. If the grid-supplied energy is majority-renewable supplied, the GHG emission reductions may be more favorable with the all-electric system as compared to the lower-cost boiler. For climates zones 1,2,3, or 4, converting more of an HVAC system's dependence on electric resistance to either heat pumps or VRF will absolutely lower GHG emissions.

In a later blog in this series, we will explore specific systems that many of our existing-building retrofit projects pursue after we discuss the role of energy modeling as a design-assist tool.

Let The Sun Make Hot Water

In the residential environment, we use fossil fuels for heating, cooking, hot water, and amenities (grills, fireplaces). In fact, 42% of residential energy load is traditionally sourced from fossil fuels. Besides the stress on the electric grid that will result if a rapid shift to all-electric homes occurred, not all buildings can easily make the adjustment. Without a doubt, starting with a blank slate and designing a building to be all-electric and energy efficient is much easier than retrofitting a historic building, or even one that is just “older”.

Yet, there is a way to make progress. At BVQ Lofts, with careful considerations of historic preservation, the building replaced wall assemblies, the roof, and doors to address air infiltration in this old building. The project also leveraged the custom window replacement program to replace the deteriorated single pane windows. By reducing air infiltration, the demand for heating (and cooling) reduces. This project sought to provide additional energy savings through a solar hot water system. The system allowed for nearly 50% annual hot water savings, though supported by high-efficiency gas-fired boilers, as the best practical backup for a central water heating system. The application of solar thermal as a heating source for hot water helps shave the reliance on fossil fuels.

Codifying Electrification With Caution

Some cities across the country are writing policies to help them achieve climate action goals, including code that requires buildings to create plans to phase-out fossil fuels and limit new construction to all-electric buildings. According to Ballotpedia, 35 of America's top cities have climate action plans. Among them is our hometown of Cleveland and other cities in which Emerald works, like Miami, Baltimore, San Francisco, Louisville, and Columbus, while New Orleans and Pittsburgh are not there yet.

Electricity traditionally costs more than fossil fuels, and that is a reality that needs to be acknowledged in this discussion. For the restauranteur who cooks with gas, the switch to electric could increase costs to produce the food by multiples of 3-5 times more. Increasing operating costs 3-5 times is not a sustainable option for businesses. Thankfully, many of these codes recognize the need to maintain reliance on fossil fuels in certain circumstances like as the source for cooking fuels.

Conclusion

In today’s environment where businesses are leading the way with action that lowers greenhouse gas emissions, any building owner is at risk for not following suit. The path to a lower-emissions profile for your existing building will be defined by the building type, age, and use, compared to capital improvement plans or renovation plans. An energy audit or energy model may be what you need to develop your path forward. Let Emerald help you find your path towards a building that contributes to your city’s climate action plan or your client’s ESG goals.

Posts by Tag

- Sustainability (174)

- sustainability consulting (147)

- Energy Efficiency (129)

- Utilities (95)

- LEED (88)

- Sustainable Design (69)

- green building certification (60)

- energy audit (48)

- ESG (47)

- construction (43)

- GHG Emissions (38)

- carbon neutrality (33)

- WELL (32)

- tax incentives (28)

- costs (27)

- net zero (27)

- energy modeling (20)

- electric vehicles (17)

- Energy Star (14)

- Housing (14)

- Inflation Reduction Act (13)

- decarbonization (13)

- water efficiency (13)

- Social Equity (12)

- diversity (10)

- NGBS (7)

- fitwel (7)

- Earth Day (6)

- Engineering (6)

- electrification (5)

- mass timber (5)

- non-profit (5)

- retro-commissioning (5)

- EcoVadis (4)

- Emerald Gives (4)

- News Releases (4)

- B Corp (3)

- COVID-19 Certification (3)

- Customers (3)

- Indoor Air Quality (3)

- PACE (3)

- Arc (2)

- DEI (2)

- EcoDistricts (2)

- Green Globes (2)

- cannabis (2)

- CDP (1)

- SITES (1)

- furniture (1)

- opportunity zone (1)

- womenleaders (1)